Slavery

Slaveryto

freedom

Study Areas

Underground Railroad

Detailed Version of Oliver C. Gilbert's Escape in 1848

Harrisburg Telegraph Version, December 1886

The story of how Oliver Kelly fled enslavement in Clarksville, Maryland during a camp meeting in 1848 with fourteen other enslaved men, traveled the back roads and through woods, evading capture, is one of bravery and daring. It is also a valuable first-person resource of names, places, events and attitudes documenting some of the inner workings of the Underground Railroad in south central Pennsylvania. Kelly himself, who took the name Oliver Gilbert after reaching freedom, told his story countless times to audiences across the state and country, as he and his family traveled and performed as the Gilbert Family Jubilee Singers. Newspaper accounts of Oliver Gilbert telling his story appear as early as 1880, and detailed printed accounts appear in newspapers, the length and degree of detail varying from paper to paper, in the mid-1880s.

The most detailed account is also one of the earliest printed, appearing in the Harrisburg, Pennsylvania Telegraph on December 4, 1886. It was written by a local correspondent who intimates that he sat down with Oliver Gilbert for an extensive interview following a performance in the city. Many of the episodes and details from this story appear in other versions printed later, often with many of the same phrases. This may represent Gilbert's storytelling style. Because he was used to telling his story in great detail to audiences at his family's concerts, the story usually following the singing, he no doubt used many rehearsed phrases, and these may be the ones jotted down by reporters and correspondents.

This is not the most definitive or complete account of his escape. Some details are missing here that appear in other versions. But it does represent a very thorough retelling of his escape from enslavement.

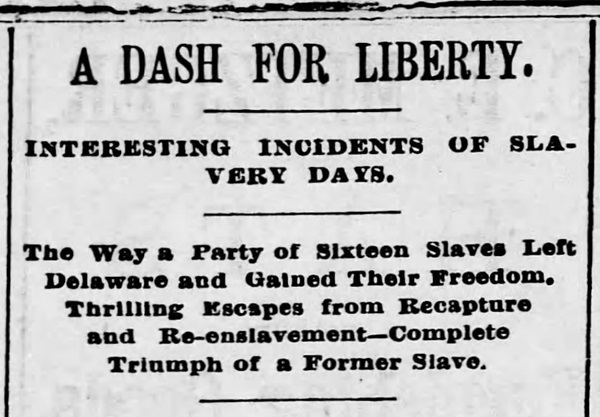

A DASH FOR LIBERTY.

INTERESTING INCIDENTS OF SLAVERY DAYS.

The Way a Party of Sixteen Slaves Left Delaware and Gained Their Freedom. Thrilling Escapes from Recapture and Re-enslavement -- Complete Triumph of a Former Slave.

Written for the TELEGRAPH.

During a concert given recently in Dauphin by the Gilbert family, of Philadelphia, Mr. Gilbert, the father of the family, gave an account of his flight for liberty. He is an intelligent man and, in addition to his knowledge of music, is a good conversationalist, thus being able to repeat with clearness and in an interesting manner the description of his daring bolt for freedom. The story was so full of romance, and was listened to with so much interest by your correspondent, that he imagined it might also be appreciated by the readers of the TELEGRAPH.

While in bondage, Oliver Gilbert was owned by Dr. Watkins, of Howard county, Maryland. In 1848, when 16 years of age, he, in company with fifteen other slaves living on adjoining plantations, laid plans for their escape. The slaves were allowed a holiday during the campmeeting season, and could remain away from the homestead from Saturday evening till Monday morning. This had been the time fixed for their departure, but on the Saturday afternoon, much to Oliver's disappointment, he was asked to inform the overseer that all the slaves except another and himself would be permitted to attend the campmeeting, and that they should remain at home, the one to take charge of the carriage to convey the master, his wife and mother to the campmeeting, while Gilbert was to accompany on horseback the daughter, who preferred to travel in that way.

Accordingly, next morning the family started and the daughter, having mounted, discovered that she had forgotten her riding whip and sent the boy to get it in a certain drawer in one of the upper rooms of the house. This obtained, both soon hurried toward the grove, and overtaking his master's carriage, he was reproved for having ridden the colt so rapidly, and although the girl explained that it had been at her direction, as she did not know it would injure the animal and had ordered him to keep up with her, her father would not be satisfied, and threatened the lad with punishment next day.

During the services Oliver cared for the horses, but was able to communicate with the rest of his party, and the unexpected turn of affairs led to a change also in their plans. Learning, however, that Rev. Mr. Brown, a strong pro slavery minister, was to preach that evening, an idea was suggested to Gilbert, and he determined to follow it out. This eminent divine wa a great favorite with the slaveholders. A firm believer himself in the system, he delighted in selecting for his text: "Exhort servants to be obedient unto their own masters, and to please them well in all things, answering not again."

He enlarged greatly upon his subject, and always took occasion to exhort the bondsmen as to their duties, etc., when they were expected to say, "Amen!" "Dat's right!" and like expressions of approval, to please their masters and create the impression that they were entirely satisfied with their lot, when the reverse was the case. The slave, therefore, was quick to observe the weak side of his master, and Oliver, knowing that a willingness to hear Rev. Brown would be the safest argument to offer for a short leave of absence, chose that method. Grandmother Watkins, always kind to the slaves, was appealed to to intercede with the master for permission to allow Oliver to stay for the evening service. His consent was obtained, though reluctantly, on account of the displeasure occasioned by the apparent abuse of the colt in the morning, and with the promise that he return early in the morning, as the oats was ready to be harvested.

During the recess taken by the white folks, the slaves, who until then stayed back, were allowed to occupy the benches, and as they sang: "I'm bound fo' de land of Canaan," the words for the sixteen had a two-fold meaning that night. Dr. Watkins' sister occupied a tent on the ground and, seeing Oliver, took him in, gave him supper, and offering him an extra biscuit, said that he would need it, as he had a long trip before him; referring, of course, to teh fifteen miles to the plantation. She also took occasion to give him some advice, saying that he should be a good boy and not run away, as his brother had done, for he had been captured and was then in jail at New Castle, Delaware. "Be a good boy," said she, "and when your master dies he will set you free." He only died four years ago, and Mr. Gilbert thinks he would have had a long time to wait. He, of course, promised to heed her advice.

About 8 o'clock the sixteen started for freedom. They continued the journey on the turnpike, running and walking, leaving it only to allow wagons and individuals to pass; startled by every sound, they hid themselves, or hurried on until they came to Westminster. Here, they knew, was stationed a patrol to catch fugitive slaves, receive the reward and return the runaways to their masters. This theylearned from a miller named Fisher, who came from Pennsylvania, with whom they conversed and who instructed them how to escape. Having passed the town in safety, they pushed on, arriving at Hanover about 8 o'clock in the morning. Here were two roads; they did not know whether to take the right or the left and dared not inquire, for it would indicate that they were strangers and excite suspicion. Having chosen the left road, they followed it for some distance and, becoming dissatisfied, ventured to ask of an old man they met where the route led to, and he replied that it would take them to Maryland, and Gettysburg was only five miles away.

Returning to the junction, they took the other road, as the old man directed, but mistrusting him they went into the woods, only to meet another on horse back, who inquired where they were going, and was told that they had been to campmeeting and were going home.

He said: "Oh! I understand; you are runaway slaves and, if you go with me, I will protect you." Their fears were thoroughly aroused by this time. They declined his kind offers of help, and he rode rapidly away. The sixteen proceeded some distance in the woods, and hid in a cornfield till toward evening. Then appearing again on the road they met two ladies, who advised them to return to the field at once, as twenty men on horses and with dogs had been hunting them. The fugitives had used something to throw the hounds off their trail, and the hunters were indignant. There was something in the manner of the ladies that indicated their truthfulness, and the slaves obeyed.

While in the cornfield, "Ben," who was their leader, ordered the boys all to examine themselves and be ready, if necessary, to kill every white man who attempted to arrest them. Oliver says he had a large dirk knife given to him by his uncle, who had obtained freedom at the death of his master, and two revolvers that he found in the bureau when he went after his young mistress' riding whip. "That," he said, "is usually called stealing, but we did not think so. The slaves often took a ham or a shoulder and enjoyed it at the quarters. It wasn't stealing; the ham and the shoulder belonged to the master adn so did we, and it was, therefore, only changing it from one place to another." Old Aunt Margaret was very much afraid of lightning, and when a storm arose, she closed the shutters, lighted a lamp and stayed in the room until is was over. To lessen the risk still more, she left the keys of the pantry in the next room, lest they should attract the electrical current. With these keys in their possession, the servants had a high time tasting the good things. They were also ordered to inform the old lady when the danger was past and, as the lightning continued to flash, they danced by the door, shouting: "De storm am not ober yet," smacking their lips as they sampled the best the shelves afforded.

In this diversion we left the fugitives in the corn field trembling, though trying to feel brave. They remained without being discovered till darkness came, and again set out on their journey, traveling all night. The next day (Tuesday) was spent partly in concealment and partly on the march. Corn fields were their favorite hiding places, and also furnished them food, for they had eaten nothing but green corn since Sunday evening. That night they came to the river at Wrightsville bridge. The gate was locked, and not being able to find a boat, they were puzzled as to how they should cross the stream. They were aware, too, that a colored man could not pass over the bridge without papers showing his liberty.

Ben, who had thus far been equal to every emergency, told the rest to hide and he would call up the gate keeper. If he demanded their "liberty papers" he would simply tell him they were at home and that he would go and bring them. They were then to wait until the old man wa asleep, batter down the gate with a log that lay close by and go on their way.

Ben carried out his part of the plan, but much to their surprise the regular toll only was asked for, which they cheerfully paid out of borrowed (?) funds, were furnished tickets for the other gate and started on the bridge. After the gate was locked behind them they began to rejoice over their good fortune in thus being admitted to the bridge, until the thought occurred to some of the party that it was only a scheme to catch them, and they were horrified at the idea of being captured when the promised land was so near. They had all along been under the impression that Canada was only ten miles from Little York, and the bridge being a mile and a quarter long, there was only that distance between them and freedom. At first their courage began to fail, but they resolved to make a final desperate struggle; which, however, was not needed, for after some delay they passed the gate and, presuming themselves to be safe in Canada, laid down in the sand on the bank and went to sleep.

They slept soundly until after daylight, when they were aroused by some one, who informed them that it was not safe to be there, and they learned for the first time that Canada was more than five hundred miles away. After spending the last cent for something to eat, they started in the direction of Lancaster, and told every person they met that they were hunting work, until an individual inquired if they were going to see "that man hung." They caught the idea that an execution was to take place in the city, and in reply to further questions as to their destination, gave that as the object of their mission.

While asking for employment they were told to call at No. 45 (name blanked) street, where they would find a friend to assist them. They complied, met the gentleman and he gave them a letter to Mr. Gibbons at Bird-in-Hand. Although still suspicious that it was only a trap to catch them, they called upon Mr. Gibbons, who was sitting on the porch with his wife, and received them very cordially. After a short conversation they were given an excellent supper, and put to bed, the best they had ever slept in. The next morning they gave him the letter they received in Lancaster, when they learned it was written by Hon. Thaddeus Stevens, the friend of the colored man. After breakfast Mr. Gibbons sent the party in a covered wagon to Chester and they separated. The family with whom Gilbert secured employment, learning his name, said that there was an Edmund Gilbert living in the neighborhood, and as he was very ill with a fever it would be well for him to visit him, as he might be a relative. He did so and found his brother, whom Mrs. Warfield had informed Oliver last Sunday evening had run away, was captured and lodged in jail. It was true, he had been in prison, but while being taken back to his master in Baltimore, who was proprietor of Barnum's Hotel, he jumped from the train and escaped, preferring to meet death, if necessary, in that way, rather than endure the punishment to be inflicted on his return.

The brother recovered and both went to Philadelphia. Oliver concluded to try his fortune in Cape May, and obtained a situation as waiter at the Columbia House. One day he saw his old master coming into the hotel, and as the Doctor appeared in one door, he disappeared through another, and fleeing to New York city he secured a like situation in a large hotel there. Here he was not safe, for one afternoon, while going upstairs with supper for a guest, he met his master's brother-in-law. Neither spoke, but, noticing that Mr. Warfield was eyeing him closely, he put the meal down and bade adieu to the place, seeking refuge among colored people in another part of the city. He afterward learned that Mr. W. telegraphed to Dr. Watkins that Oliver worked at the hotel where he was staying, and received an immediate reply to have him apprehended and sent on, but by that time he was not to be found.

From New York he went to Brooklyn, and then to Boston, where he found plenty of friends. This was in 1850, and he remained in the service of Mr. Gilbert, a piano manufacturer, until the year 1854. At that time it was not safe for him even in Boston, and he fled to England; staying there until 1859, he came back to Boston and went into the office of Wm. Lloyd Garrison for about a year; then to Saratoga; there he was married in 1860 and lived until 1876, finally moving to Philadelphia, where he now resides.

About ten years ago, as the president of a campaign organization of colored men, he wrote an address to his people instructing them as to their duty, etc., at the approaching election. One of these letters he sent to his former master, which opened up a correspondence and led to an invitation to visit the old plantation. This he did, and was very heartily received by the Doctor and his children. Besides the cordial welcome, Mr. Gilbert was given an opportunity to speak in public, with the privilege of choosing his own subject. The hall was crowded, and occupying seats upon the stage were his master and other prominent ex-slaveholders. He was introduced by Dr. Watkins as his runaway slave, and astonished them by an excellent address upon "The rise and fall of slavery."

The Doctor also told him that after his escape he felt rather indignant, but now, seeing what progress he had made, he would forgive all, and expressed his intention to visit him, but died before his plans were carried out. He has met the children since, and they appear glad to see him, to know that a former slave could so improve, and be of so much use in the world, for it may be added that Mr. Gilbert has spent much time and money for the elevation of his race.

A.T.P.

Notes

The headline shown above for this news feature incorrectly reports the escape from Delaware, instead of Maryland.

The writer, "A.T.P." is so far unidentified. While the writer reports most of the story details impassively, some passages incorporate racist stereotypes, language and attitudes, which were quite common even in publications such as The Telegraph that were sympathetic to the idea of social, legal and political equality for African Americans.

Oliver Cromwell Gilbert was born enslaved in Clarksville, Maryland as Oliver Cromwell Kelly. His father, Joseph Kelly, was a free Black man in Owingsville, Maryland, but his mother, Cynthia Snowden, was enslaved, and Oliver shared that status upon birth. He produced important writings and documents on his experiences, many of which are archived at the University of Maryland, the Maryland Historical Society and the University of New Hampshire. A descendant, Stephanie Gilbert, maintains an excellent website devoted to his life and work, "Olver Cromwell "O.C." Gilbert, at https://ocgilbert.com/.

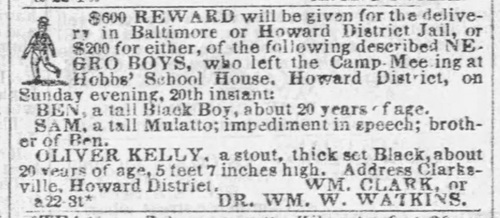

Oliver Kelly took the surname "Gilbert" from Lancaster County farmer Amos Gilbert, one of the Bart Township Quakers that aided him in his escape. In the fugitive slave advertisement below, he is listed by his enslaver, Dr. William Watkins, as Oliver Kelly.

Text of the ad above:

$600 REWARD will be given for the delivery in Baltimore or Howard District Jail, or $200 for either, of the following described NEGRO BOYS, who left the Camp-Meeting at Hobbs' School House, Howard District, on Sunday evening, 20th instant:

For a shorter version of this story that appeared in Lancaster area newspapers in 1887, see thia page.

BEN, a tall Black Boy, about 20 yeares of age.

SAM, a tall Mulatto; impediment in speech; brother of Ben.

OLIVER KELLY, a stout, thick set Black, about 20 years of age, 5 feet 7 inches high. Address Clarksville, Howard District.

WM. CLARK, or

DR. WM. W. WATKINS.

Sources

- The Baltimore Sun, 23 August 1848.

- The Inquirer (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), 26 February 1887.

- The Lancaster New Era (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), 26 February 1887.

- The Telegraph (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania), 04 December 1886.

- The Madison Eagle (Madison, New Jersey), 09 May 1885.

- Life & Legacy, O.C. Gilbert, https://ocgilbert.com/about/, accessed 14 May 2024.

Now Available on this site

The Year of Jubilee

Vol. 1: Men of God and Vol. 2: Men of Muscle

by George F. Nagle

Both volumes of the Afrolumens book are now available on this website. Click the link to read.

The Year of Jubilee is the story of Harrisburg'g free African American community, from the era of colonialism and slavery to hard-won freedom.

Volume

One, Men of God, covers the turbulent beginnings of this community,

from Hercules and the first slaves, the growth of slavery in central

Pennsylvania, the Harrisburg area slave plantations, early runaway

slaves, to the birth of a free black community. Men of God is a detailed

history of Harrisburg's first black entrepreneurs, the early black

churches, the first black neighborhoods, and the maturing of the social

institutions that supported this vibrant community.

Volume

One, Men of God, covers the turbulent beginnings of this community,

from Hercules and the first slaves, the growth of slavery in central

Pennsylvania, the Harrisburg area slave plantations, early runaway

slaves, to the birth of a free black community. Men of God is a detailed

history of Harrisburg's first black entrepreneurs, the early black

churches, the first black neighborhoods, and the maturing of the social

institutions that supported this vibrant community.

It includes an extensive examination of state and federal laws governing slave ownership and the recovery of runaway slaves, the growth of the colonization movement, anti-colonization efforts, anti-slavery, abolitionism and radical abolitionism. It concludes with the complex relationship between Harrisburg's black and white abolitionists, and details the efforts and activities of each group as they worked separately at first, then learned to cooperate in fighting against slavery. Read it here.

Non-fiction, history. 607 pages, softcover.

Volume

Two, Men of Muscle takes the story from 1850 and the Fugitive Slave

Law of 1850, through the explosive 1850s to the coming of Civil War

to central Pennsylvania. In this volume, Harrisburg's African American

community weathers kidnappings, raids, riots, plots, murders, intimidation,

and the coming of war. Caught between hostile Union soldiers and deadly

Confederate soldiers, they ultimately had to choose between fleeing

or fighting. This is the story of that choice.

Volume

Two, Men of Muscle takes the story from 1850 and the Fugitive Slave

Law of 1850, through the explosive 1850s to the coming of Civil War

to central Pennsylvania. In this volume, Harrisburg's African American

community weathers kidnappings, raids, riots, plots, murders, intimidation,

and the coming of war. Caught between hostile Union soldiers and deadly

Confederate soldiers, they ultimately had to choose between fleeing

or fighting. This is the story of that choice.

Non-fiction, history. 630 pages, softcover.